Johan Maurits

On this page we take a closer look at Johan Maurits and his historical relationship with the building and the Mauritshuis collection. We also share how we as the Mauritshuis organisation view Johan Maurits in the present day, what research is currently being undertaken into Johan Maurits and in which form we wish to communicate this information with our visitors.

Johan Maurits

The name Mauritshuis literally means: Maurits’s house. The museum owes its name to the man who commissioned the building and was its first owner: Johan Maurits, Count of Nassau-Siegen (1604-1679), who was born in Dillenburg Castle in Germany in 1604. This makes him, like his great uncle William the Silent, a German nobleman. Johan Maurits was only 16 years old when he started his military career as an officer in the army led by the stadholder Maurits of Nassau. It is this Maurits who often comes to mind when the Mauritshuis name is mentioned, although the association really is with his – lesser known – German cousin Johan Maurits. It was the latter who purchased a plot of land alongside the Binnenhof with the intention of building a grand residence. His future neighbour was Constantijn Huygens, secretary to the stadholder and a friend for life.

Johan Maurits and Brazil

The construction of the Mauritshuis (1633-1644) largely took place while its future occupant was abroad: in October 1636 Johan Maurits set sail for Brazil to take up the position of Governor-General of the colony ‘Dutch Brazil’ in the service of the Dutch West India Company (WIC). He owed this prestigious appointment to his family connection to stadholder Frederik Hendrik, who had succeeded his half-brother Maurits.

The colony consisted of a coastal area in the north-east of Brazil that the WIC had captured from the Portuguese in 1630. The Portuguese had set up a lucrative sugar industry there, with sugar cane plantations and sugar mills that were reliant on the labour of enslaved Africans. ‘Dutch Brazil’ became the first large Dutch plantation colony in the Atlantic area.

At first, the Dutch regarded slavery as an ‘unchristian’ act perpetrated by their Catholic Spanish and Portuguese enemies. But with the arrival of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in ‘the East’ and the WIC in ‘the West’, the Dutch too started to use slave labour outside the borders of the Dutch Republic. There were a number of Dutch individuals in the early decades of the 17th century, including pastors but also administrators, who spoke out against inhumane slavery, but the beckoning profits silenced their criticism. Both the VOC and the WIC started to use and trade in enslaved people. The first area where this happened on a large scale under Dutch authority was Dutch Brazil. This makes the period that the Dutch were in Brazil (1630-1654) a crucial episode in the Dutch history of slavery. Suriname, where the highest number of enslaved people were deployed, would follow later in the 17th century.

Johan Maurits occupies a central role in this history. After his arrival in Brazil, he revived the plantation economy by providing loans to the Portuguese to take over and run the abandoned sugar mills. The governor was reliant on the Portuguese who had stayed behind – there were too few Dutch able or willing to take over their work. Another problem was the hard daily labour: the mills had to run around the clock and who was going to do that? As early as 1637, the governor equipped a fleet tasked with capturing the Portuguese trading post Elmina Castle (Ghana) on the west coast of Africa. Three years later, Johan Maurits sent another fleet and the city of Luanda (Angola) was captured from the Portuguese. These locations were among the most important slave depots at that time. As such, Johan Maurits, under the orders of the WIC, brought the Dutch into the slave trade.

But Johan Maurits was not only at the head of a society that ran on slave labour, he was also personally involved in slavery and the slave trade. Many enslaved Africans worked at his court. Johan Maurits also profited from the sale of Africans who had been given to him as a gift by the king of Congo. Finally – in collaboration with Portuguese at his court – he also smuggled enslaved people into Brazil. Exactly how much money he earned from doing so is impossible to ascertain, particularly given the illegality of smuggling activities in the eyes of the WIC. What is known is that Johan Maurits spent huge sums on his palaces and court. He later declared that his two houses in Brazil together cost at least 150,000 guilders, and he also lent another 75,000 guilders to Portuguese in the colony. By way of comparison: Johan Maurits’s annual salary at this time was 21,600 guilders. It is clear that Johan Maurits seized every opportunity to earn more money, which included not shying away from the slave trade.

Although slavery is inextricably linked with Dutch Brazil, this is rarely reflected in the historical perception of Johan Maurits. Traditionally, the governor has above all been remembered for his love of the arts and science, as well as for his enthusiasm for building. In Recife and Mauritsstad he laid out gardens and had buildings erected, and even today some of the infrastructure is still reminiscent of Johan Maurits. He has also often been praised for his administration, in which there was a far-reaching degree of participation, and for his tolerance of religious faiths other than the prevailing Calvinism which he himself practised.

After his time in Brazil, his administration in Cleves was similarly characterised by a tolerant attitude towards Catholics and Jews. In Brazil, Johan Maurits had also demonstrated religious leniency towards these two groups in particular. This was conspicuous when his contemporaries and fellow Calvinists – Peter Stuyvestant in New Netherland and Kan Pieterszoon Coen in Batavia – had done precisely the opposite.

All the same, we should not overestimate Johan Maurits’s tolerance which was more pragmatic in nature than it was ethical: he needed the Portuguese Catholics and Jews to keep sugar production going. Unlike many other colonial areas, the Portuguese population remained largely present after the capture of the Portuguese province by the WIC. It would have been foolish to drive them away. Johan Maurits could not do without them: their presence as owners of the sugar mills and therefore as connecting factors in the sugar industry and the slave trade was crucial for maintaining the economy.

In 1643, the directors of the WIC – the Heeren XIX (the Nineteen Gentlemen) – called Johan Maurits back to the Dutch Republic and in 1644 his governorship came to an end. The Dutch troops in Brazil had to be scaled back and there was annoyance among the Heeren XIX at the extravagance and lust for construction displayed by the governor who presided over a royal court in Brazil.

Today, as in the past, the prevailing image of Johan Maurits’s governorship is often defined by the aspects that can be recognised as positive. This is also true of Brazil, where Johan Maurits even enjoys hero status among some. Reference is made, for example, to how the local rulers in Brazil asked Johan Maurits to stay on, or to the crowds of people who are said to have waved him off when he left. These stories aside, Johan Maurits’s present-day popularity in Brazil has much to do with a more general dislike of the Portuguese coloniser. The Portuguese made a firm mark on Brazil, both before and long after the Dutch, particularly through the large-scale slave trade. It therefore comes as no surprise that the relatively short period that the Dutch spent in Brazil, characterised by exceptional religious tolerance and the practice of art and science, is considered by many as a positive note.

The artistic and scientific legacy of Johan Maurits’s time in Brazil is unquestionably invaluable. Johan Maurits was accompanied on his journey to Brazil by a group of artists and scientists who would study and record the landscape, inhabitants and flora and fauna in a large number of maps, drawings, prints and paintings. They included the physician Willem Piso, physicist Georg Marcgraf and artists Frans Post and Albert Eckhout. The publication in 1648 of Historia Naturalis Brasilia, the first scientific reference book about Brazil, is of particular interest in this respect. Also important was the Rerum per octennium in Brasiliae […] (1648) that Caspar Barlaeus was commissioned to write by Johan Maurits. Barlaeus himself had never visited Brazil, but was able to make use of documents and material produced by others. The book describes Johan Maurits’s feats in Brazil and is illustrated with wonderful prints and maps. Although it forms an important source, it should not be viewed as an objective history: Johan Maurits not only financed the book, he also influenced the content.

Johan Maurits and the Mauritshuis collection

The name ‘Mauritshuis’ often gives the impression that Johan Maurits’s collection is on display in the museum – this is not the case. The core of the Mauritshuis collection comes from the collection of stadholder William V Nevertheless, there are a few works in the museum collection that were once owned by Johan Maurits: a portrait of him by the Hague painter Jan de Baen, and two paintings made by artists who visited Brazil as part of his retinue. These are Study of Two Brazilian Tortoises from c. 1640, which is attributed to Albert Eckhout, and Frans Post’s View of Itamaracá Island in Brazil from 1637 (on long-term loan from the Rijksmuseum). Frans Post continued to paint Brazilian landscapes after he had returned to the Dutch Republic, a beautiful example of which can also be found in the collection. He was able to elaborate on this theme for a long time – clearly the genre appealed to buyers.

A number of other works and paintings that we know were once owned by Johan Maurits and which were possibly displayed in the 17th-century Mauritshuis were disposed of by Johan Maurits himself. The most important group consists of 24 paintings that are now in the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. Johan Maurits gave them to the King of Denmark, Frederick III, in 1654: twelve still lifes with tropical fruit and plants, a painting with a dancing Tarairiu, eight large paintings by Eckhout portraying the representatives of various communities in Brazil, and three portraits of men from Congo. The Elector of Brandenburg purchased hundreds of drawings in 1652, which are now in Krakow. King Louis XIV also received a group of artworks as a gift from Johan Maurits in 1679, including a number of cartoons that would later be transformed into a series of monumental tapestries.

A new permanent room dedicated to Johan Maurits (2020)

In today’s Mauritshuis there is very little to see of the founder and first inhabitant of the 17th-century house. Nevertheless, the Mauritshuis would like to tell its visitors the story of the museum’s background, where the Mauritshuis name comes from and who Johan Maurits was. Because Johan Maurits was the person who laid the house’s first stone, the person who lived here and the person who walked through these rooms and welcomed high-ranking guests. He introduced them to Brazil, to objects made by the people who lived there and to the animals and plants that flourished there. He opened his guests’ eyes to a continent that was entirely unknown in the Netherlands in the mid-17th century. The name Mauritshuis is therefore in no way a tribute to Johan Maurits, but a historical designation. This was his house.

In September 2020, a room was permanently installed to share the story of the relationship between the museum’s name giver and the building with visitors. A number of paintings from the museum’s collection look at Johan Maurits as an individual and at his presence in the Dutch colony in Brazil. On display are the paintings by Post and Eckhout mentioned earlier and the portrait of Johan Maurits by Jan De Baen. This painting was purchased by King William I shortly before the Mauritshuis became a museum in 1822, especially to supplement the museum’s collection.

The works displayed in the room only show one side of the story. The bright side. The paintings do not testify to the immense human suffering endured on the journey from Luanda or Elmina to Brazil, to the loss of family, hearth and home, or to hardship, humiliation, rape and death. Nor do they show the suffering of the other communities and professions. The paintings only present the image that people wanted to see of the overseas territory. Naturally, we point out the absence of these images in the paintings to our visitors.

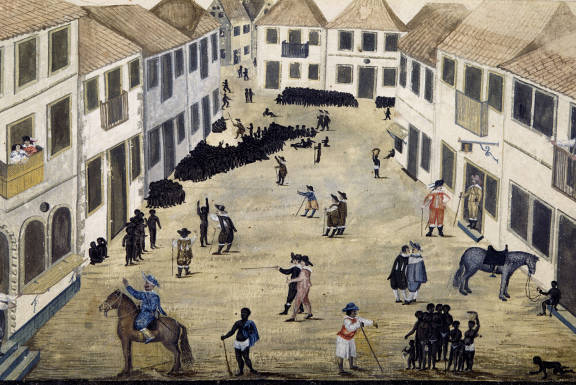

Zacharias Wagner, a soldier in the service of the WIC during Johan Maurits’s Brazilian period, did record the other, harsher side of Dutch Brazil in sketches he made in a private book. These show the slave market in Recife, for example, and a woman with the monogram of Johan Maurits branded on her chest.(

Long-term academic research project

The Mauritshuis has focused on Johan Maurits in exhibitions held in 1979/80, 2004 and 2019. In the 1979 exhibition As Far As The World Reaches the emphasis lay for the most part on Johan Maurits’s importance for the arts, architecture and science. In 2004, a monographic exhibition was dedicated to the work of Albert Eckhout. Johan Maurits’s interconnectedness with colonial history, particularly the transatlantic slave trade, came more to the fore in the 2019 exhibition: Shifting Image – In Search of Johan Maurits. This exhibition explored how Johan Maurits’s history can be viewed from different perspectives.

The intention with Shifting Image was not to present a historical overview. Indeed, both during and after this exhibition, we became aware that many research questions still remained. Which is why the Mauritshuis started an inventory of sources in 2018, which in 2020 was followed by a long-term research project Revisiting Dutch Brazil and Johan Maurits, which you can read more about here.

Continue reading