19. You're cracking me up

The Girl must have been young when Vermeer painted her, but just as people develop wrinkles as they get older, paintings start to show their age in the form of cracks. The network of cracks that forms on a painting over time is also known as ‘craquelure’. It can be seen as a desirable part of the ageing process: a sign that the Girl has been around for more than 350 years.

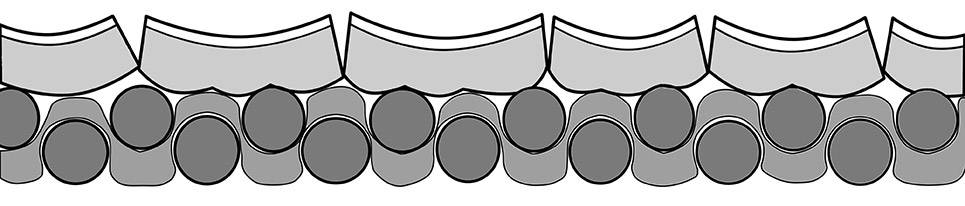

Why do age cracks form? Over time, the paint and ground layers become less flexible and more brittle. If the temperature and humidity of the environment around the painting isn’t kept stable, the canvas shrinks and relaxes. This creates stresses in the ground and paint layers, and to relieve this stress, the layers crack. If the canvas shrinks a lot, the edges of each flake lifts up: a phenomenon known as ‘cupping’. If a flake of ground and paint comes unstuck from the canvas, it leaves a paint loss.

Ground-breaking research

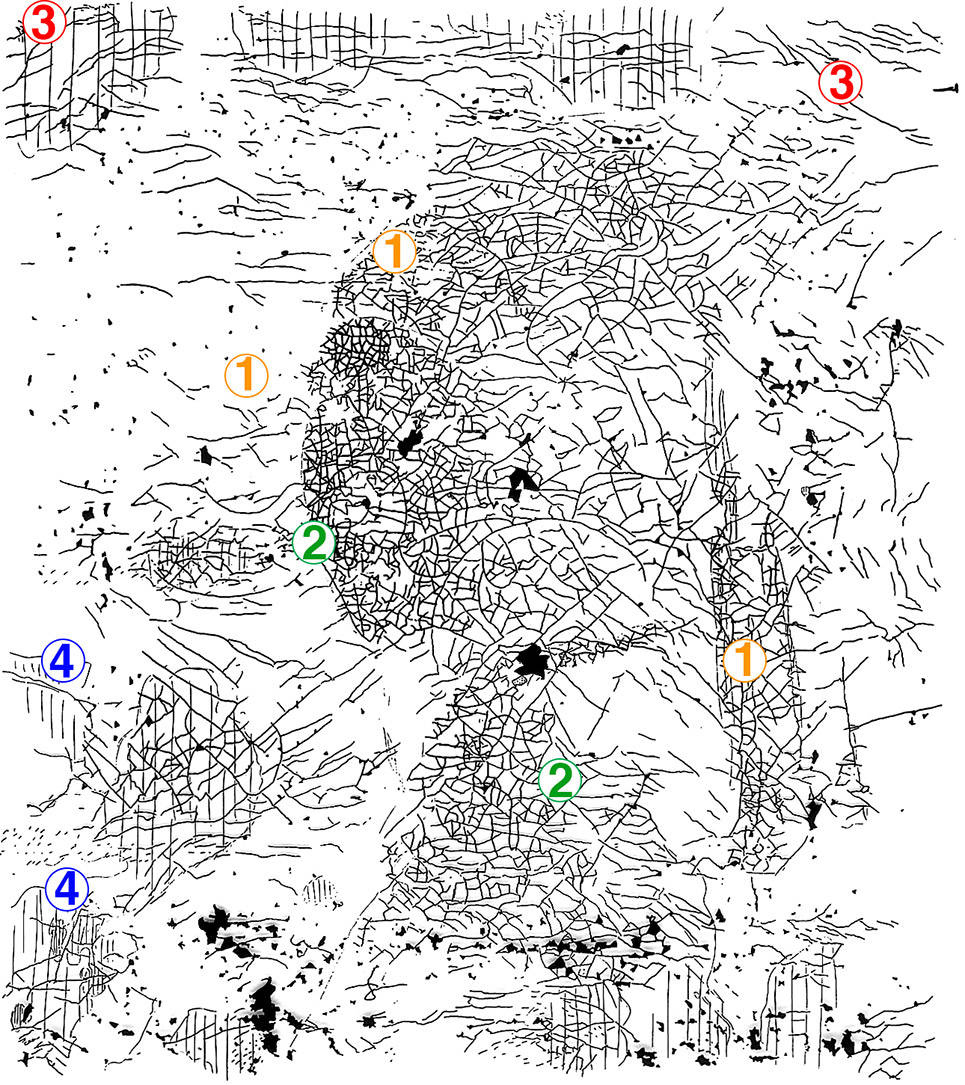

Cracks aren’t something that conservators spend much time studying as part of a typical treatment, but the ones in the Girl were of interest to the team who restored her in 1994. Jørgen Wadum, one of the conservators, made a diagram of the different types of cracks in the Girl, and what might have caused them:

- Strong pattern of age cracks,

- Spider web pattern, caused by pressure or sudden impact,

- In the corners: when the keys in the corner of the stretcher were tapped too hard,

- Fine cracks in the ground layer, formed soon after the ground was applied.

The 1994 researchers wondered why the cracks were so wide and dark in the Girl’s face. Some of it was caused by previous restoration treatments that were supposed to help the cracking, but sometimes did more harm than good.

The 1882 restoration probably used a water-based lining adhesive that made the original canvas shrink. This caused cupping in the paint and ground, and some paint losses. When the painting was restored again in 1915, the varnish was ‘regenerated’ with materials that might have caused further harm, including a tree resin called copaiba balsam. This was detected when the 1994 researchers analysed black material in the cracks.

A new look at the cracks

During the recent Girl in the Spotlight examination, our scientific instruments revealed different aspects of the cracks. A raking light photo (see above) shows the 3-dimensional relief of the painting, including the craquelure and slight cupping of the paint.

If tiny pieces of paint and ground become detached from the canvas, fragments flake off, leaving paint losses. On the x-ray, these appear black. The losses aren’t visible to the naked eye because they were carefully filled and retouched during the 1994 treatment. (As I mentioned in the blog about conservation history, some of the detached fragments got stuck in the varnish, and were saved as paint samples.)

Colour/topography

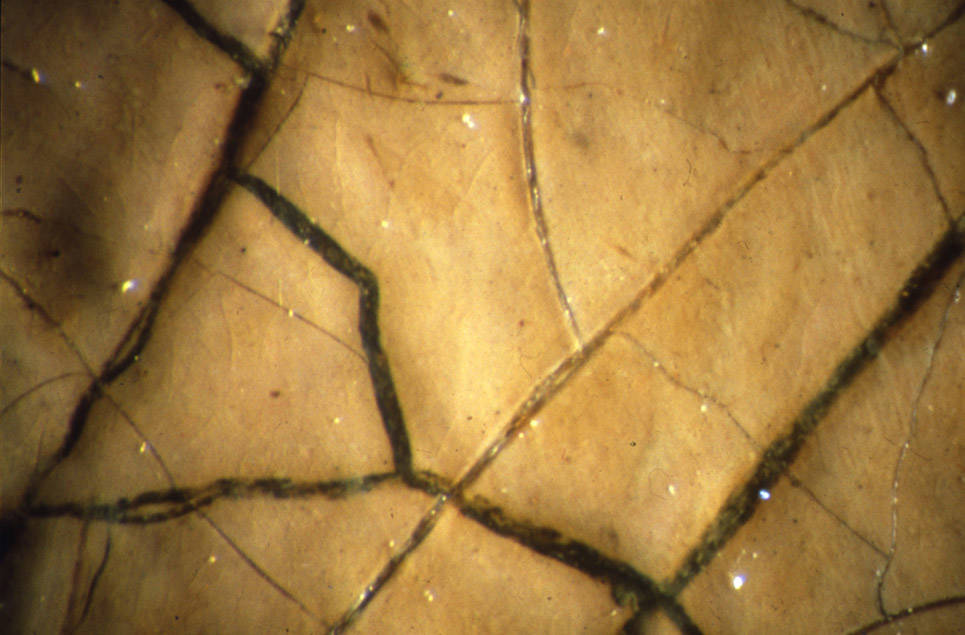

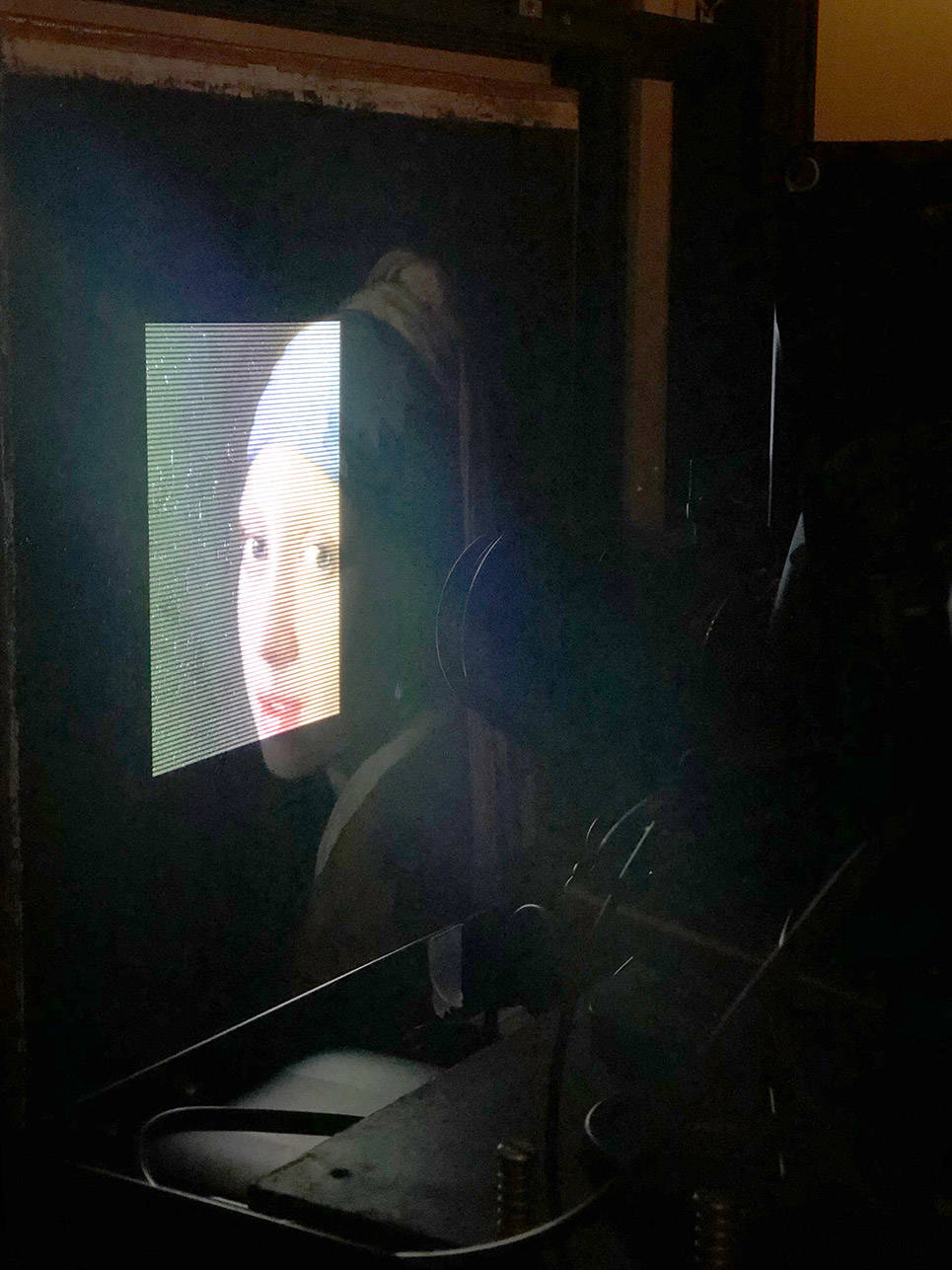

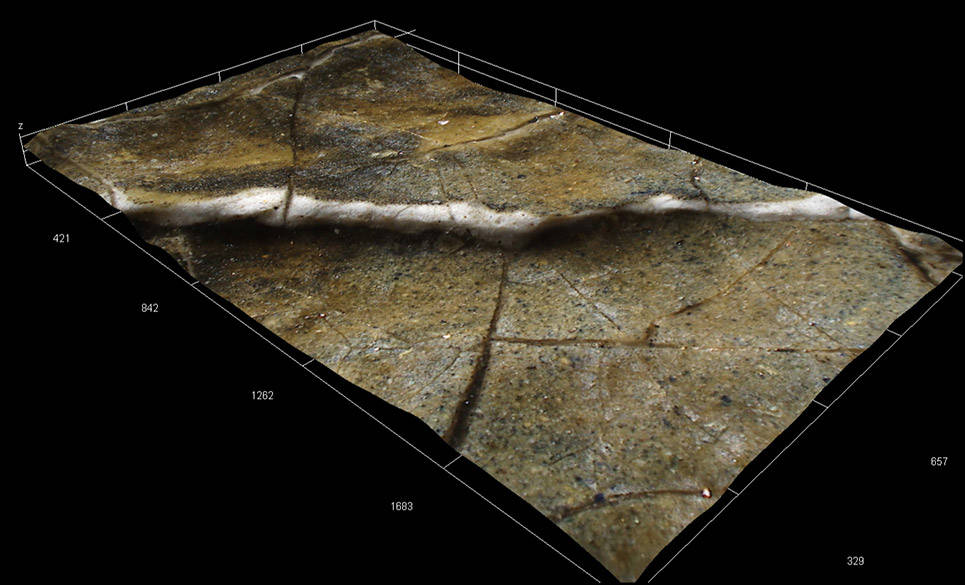

The Colour/Topography scanner used by Mathijs van Hengstum from TU Delft collects information about the crack pattern at a microscopic level in ultra-high resolution. A projector projects fine vertical and horizontal lines onto the painting, which are captured by two cameras positioned on either side. The deviations in the lines are translated by a computer into topographical information about the painting. The Colour/Gloss/Topography scanner used by Willemijn Elkhuizen from TU Delft detects differences in gloss., as well as the colour and topography. This is especially relevant in the background of the Girl. We know that originally this background was a dark greenish-black, but the colour and gloss have changed over time, making it look greyish and patchy. The Hirox hybrid 3d digital microscope captures images of the 3D surface of the painting. The cracks are visible as peaks and valleys.

It’s important to document the current appearance of the cracks. If and when the Girl is examined in the future, we can see whether the cracks have changed. An important part of conservation research is understanding what has happened to a work of art throughout its life, and how it can potentially change in the future. Well-intended restoration treatments of the past ¬– aqueous lining, regenerating varnish layers – may have exacerbated some problems, but conservation has been vital to extending the life of a masterpiece that was virtually unrecognised a century ago. The Mauritshuis preserves the Girl with a Pearl Earring and the other works in its collection by maintaining a stable environment, protecting paintings behind UV-filtering glass, doing regular checks, and carrying out conservation and restoration treatments when necessary. We will continue to monitor the Girl to make sure she stays in stable condition. Despite subtle changes, her beauty shines through.

References

- Bucklow, Spike, The Classification of Craquelure, Hamilton Kerr Institute.

- Flores, J.C. (2017) ‘Mean-field crack networks on desiccated films and their applications: Girl with a Pearl Earring,’ Soft Matter, 13, pp. 1352-1356.

- Noble, Petria and Epco Runia (2009) Preserving our Heritage: Conservation, Restoration and Technical Research in the Mauritshuis, Waanders, p. 184.

- Groen, Karin M., Van der Werf, Inez D., Van den Berg, Klaas Jan, Boon, Jaap ‘Scientific examination of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring,’ In: Vermeer Studies: Studies in the History of Art, edited by Ivan Gaskell and Michiel Jonker, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., Yale University Press, New Haven/London, 1998. [online version]

Acknowledgements

- X-ray and technical photography: René Gerritsen (René Gerritsen Art & Research Photography)

- Digital microscopy: Emilien Leonhardt and Vincent Sabatier (Hirox Europe)

- Ultra-high resultion Colour/Topography scanning: Mathijs van Hengstum, Yu Song (TU Delft)

- Colour/Gloss/Topography scanning: Willemijn Elkhuizen, Tessa Essers, Jo Geraedts (TU Delft)

- Jørgen Wadum (CATS at Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen / formerly Mauritshuis)