9. Watching paint dry

How did Vermeer make the paint that was used in the Girl with a Pearl Earring? Like most 17th century Dutch artists, he used oil paint. Paint is made from pigments (coloured powders) mixed with a binding medium to make a thick, soft paste. The next few blog entries will be devoted to the pigments that Vermeer used to make different colours, and where they came from, but first, let’s hear about his oil.

Oil change

The binding medium used to paint the Girl is linseed oil, made from the seeds of the flax plant. As I mentioned in the blog about canvas, flax stems were used to make linen for canvas, and the seeds of the plant (linseeds) were pressed to make oil.

Linseed oil was identified in the Girlby analysing samples using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). Remarkably, GC-MS found that the oil in the background also contains a tiny amount of rapeseed oil. We don’t yet know much about the use of rapeseed oil in paintings, since it isn’t mentioned in historical recipes. It’s unlikely that Vermeer added this himself. Maybe the rapeseed was a contamination of linseed oil, as windmills were probably used to press oil from different sources.

In 17th century Netherlands, linseeds were commonly pressed using a windmill. At the Dutch oil mill Het Pink, you can see this process for yourself:

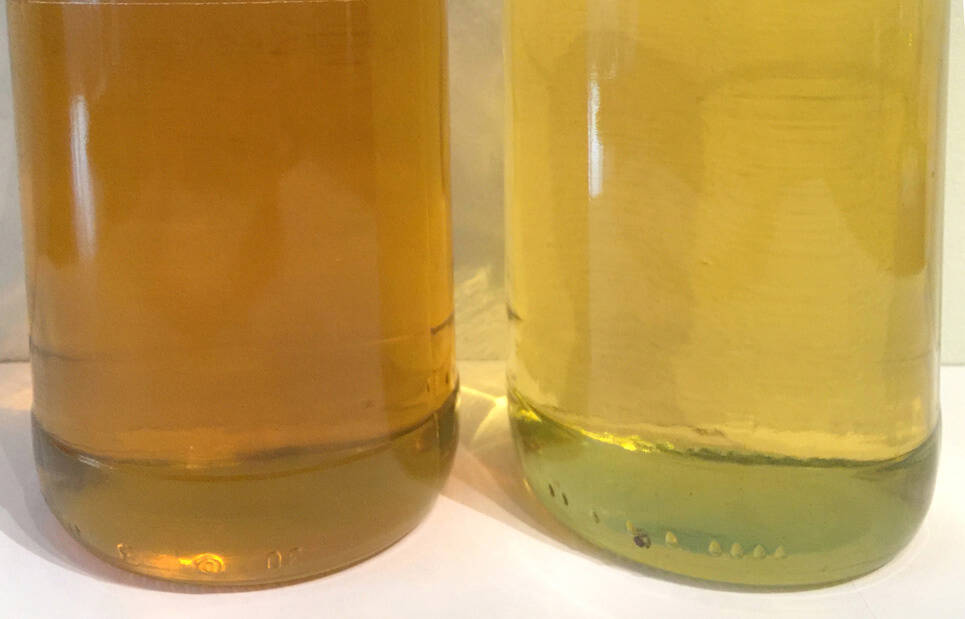

I bought some linseed oil from Het Pink to make paint, and left it in an open container on the windowsill for a year. Leaving oil to sit in the sun makes it a better binding medium for two reasons. The oil turns from a brownish to light yellow colour – which is better for the eventual colour of the paint. It also makes the oil thicker (more viscous).

It seems that Vermeer bought – or maybe even made – a specific type of oil that allowed him to control how thick his paint was, and how fast it dried. Analysis with GC-MS showed that the oil was slightly heat-bodied. Heating oil to a high temperature (around 300°C, usually with added dryers) would have changed its painting properties, making it smoother, glossier, easier to paint with, and perhaps faster drying.

Drying

Linseed oil – unlike olive oil or vegetable oil – is a ‘drying oil’, meaning that it can set to form a stiff, rubbery film. When it is used to make oil paint, it dries at different rates depending on which pigment(s) are chosen.

If you’ve ever made an oil painting, you’ll know that it doesn’t dry right away. You can move the paint around with your brush for minutes, or even hours after you’ve applied it. The slow drying speed of oil paint allowed Vermeer to blend colours together in the Girl, and to manipulate his paint after he applied it. To achieve the subtle blending from light to shadow, for example the translucent skin on the edge of her cheek, he used a soft dry brush to blend the wet paint after he applied it.

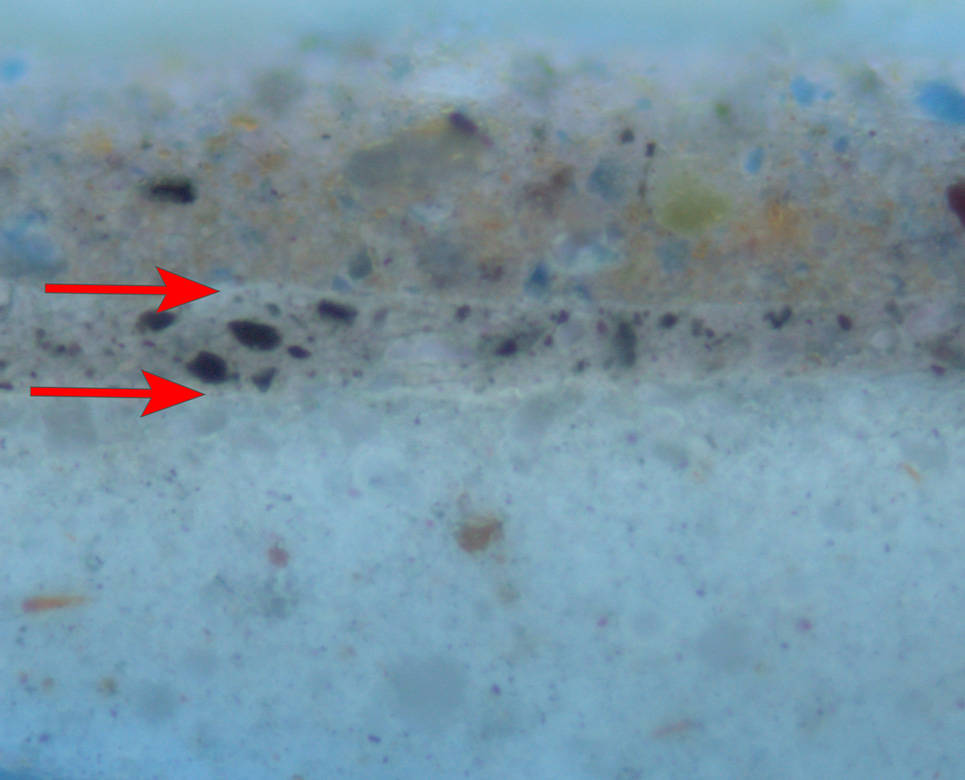

The slow drying speed of oil paint allowed Vermeer to blend colours together, and to manipulate his paint after he applied it. On the other hand, without the help of dryers, some coloured paints would take forever to harden. This would have made it impossible to layer one colour on top of another. Oil paints dry at different rates depending on which pigment(s) are chosen. In his 17th-century ‘painter’s manual,’ Theodore De Mayerne listed the drying times of different pigments, including: umber (2-3 hours), lakes (5-6 days), and that black paints will never dry unless they had been modified with a dryer. Samples from the Girl were analysed using SEM-EDX, which detected lead in some of his dark paints.

Vermeer let some layers dry thoroughly before he applied more paint on top. Most cross-sections show a distinct separation between layers of paint.

Oil + pigment = paint

Vermeer couldn’t have bought tubes of paint from an art supply store. He (or an assistant) ground the pigment and oil together on a stone slab using a muller to make a thick, soft paste. Different pigments required different amounts of oil, so preparing paint took training and practice.

Paint tubes weren’t patented until the 19th century. In Vermeer’s time, small quantities of prepared paint were kept in covered pots, or in animal bladders. When an artist was ready to use the paint, he could prick the bladder with a needle, and squeeze out a small amount onto his palette.

Tomorrow’s blog will explore where Vermeer bought his painting materials.

Referenties

- Oil mill Het Pink in Koog aan de Zaan, the Netherlands.

- Oil paint (Wikipedia)

- Gifford, E. Melanie and Lisha Deming Glinsman (2017) ‘Collective style and personal manner: Materials and techniques of high-life genre paintings.’ In: Vermeer and the masters of genre painting: Inspiration and rivalry, Adriaan E. Waiboer et al. (eds.), Yale University Press.

Acknowledgements

- Research into oil: Indra Kneepkens (University of Amsterdam)

- Binding medium analysis (GCMS 1994-96): W.G. Th. Roelofs (Centraal Laboratorium (now RCE)); (PY-TMAH- GCMS and DTMS, 1996): Inez D. van der Werf, Klaas Jan van den Berg and Jaap Boon (FOM Institute for Atomic and Molecular Physics (AMOLF))

- Binding medium analysis (PY-TMAH-GCMS and DTMS, 1994-96): W.G. Th. Roelofs (Centraal Laboratorium (now RCE)); Jaap Boon (FOM Institute for Atomic and Molecular Physics (AMOLF))

- SIMS analysis of thin layers: Anne Bruinen and Ron Heeren (Maastricht University)