Cannon of Kandy

In the exhibition we show a video, in which you see the creation of a 3D model of the cannon of Kandy. The model is stored on the hard drive in the vitrine.

The original decorative cannon was looted in 1765 from the palace of Kandy, in central Sri Lanka (Ceylon). By that time, the island’s coastal areas had been occupied for over 100 years by the Dutch East India Company (VOC), which profited greatly from the cinnamon trade.

During the Dutch occupation, the people revolted several times against exploitation and forced labour. The open support given by the King of Kandy, Kirti Sri Rajasingha, to the popular uprising of 1761 marked the beginning of a guerrilla war that lasted for years. In 1765, Kandy was briefly conquered by VOC troops led by Governor Van Eck. All valuables were either looted or destroyed. Faced with continuous Kandyan resistance, the Dutch eventually retreated. The cannon was taken as loot.

The cannon was shipped to the Netherlands and added to the collection of stadholder William V. In 1795, most of this collection was confiscated by French revolutionary troops and carried off to Paris, but the cannon stayed in the Netherlands. In 1825, it was added to the collection of the Royal Cabinet of Rarities, which was housed in the Mauritshuis. In 1875, it was transferred to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

Since 1964, Sri Lanka has made several requests for the cannon to be returned. These repeated requests, the most recent of which was made in 2022, has finally been honoured in 2023. Once the cannon is back in Sri Lanka, the 3D model you are now looking at is all that will be left in the Netherlands.

Reproductions such as these raise questions about intellectual property and the autonomy of works of art: are digital models simply copies of original pieces, or do these virtual objects have an intrinsic value of their own? Can digital files ever belong to a single owner, or should they be treated as world heritage? It is necessary that we work together to find answers to these questions.

Return

Sri Lanka has been calling for the return of this cannon since 1964. The most recent request from 2022, has now been granted. On 28 August 2023, the Netherlands officially transferred ownership of the cannon to Sri Lanka.

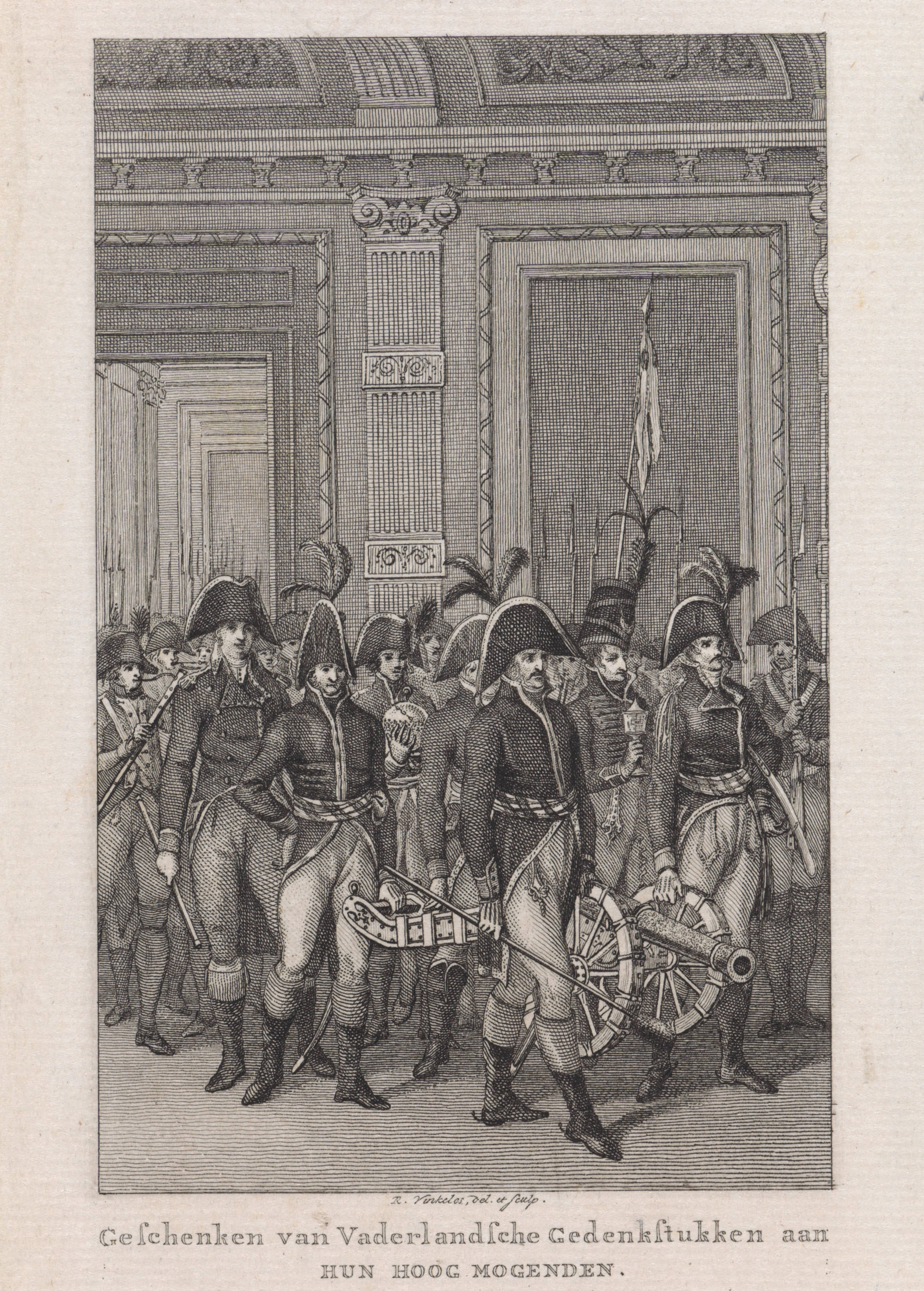

In the past, claims were rejected based on the incorrect assumption that the cannon had been gifted to the Dutch stadholder by the King of Kandy. This assumption stemmed from a misinterpretation – dating back to 1894 – of the inscription on the cannon. After in-depth research into the historical artefact’s provenance, the inscription has now been placed in the right context: the cannon was a gift to the King of Kandy and was looted by the Dutch in 1765. Now that it has been conclusively established that the cannon was taken as a war trophy, it has been unconditionally returned to Sri Lanka.

International cooperation

To research the cannon, it was essential to collaborate with experts from Sri Lanka, the UK and the Netherlands. Expertise on 18th-century Kandyan art, crafts, weapons and inscriptions is scarce in the Netherlands. Conversely, Dutch archives are difficult for Sri Lankan researchers to access because of the language barrier and physical distance. The joint study of photographs of inscriptions and decorations eventually led to a better understanding of the cannon’s history and yielded answers to questions about its provenance.

Historical and artistic value

The cannon has both Kandyan and European features. The winged angels, acanthus leaves and dolphin-shaped handles are part of the original 17th-century European design, while the Sri Lankan decorations were added later. This style brings together various influences from the Indian Ocean region. The Kandyan artists responded to the earlier European decorations by adding their own motifs. Since the cannon was intended as a diplomatic gift, they also added a special decoration wishing the recipient good fortune. The decorated cannon is one of the few remaining examples of this artistic style and is therefore of great art historical importance.

Download Image

Non-commercial use

All our images can be downloaded in high resolution from our website for non-commercial use (research/study, educational purposes, personal blogs and social media).

Would you like to use our images in a publication? Please mention our credit line: "Mauritshuis, The Hague."

Commercial use

Would you like to use our images for commercial purposes? We would be happy to discuss this with you. Please contact our marketing department at [email protected].

Download Image

Non-commercial use

All our images can be downloaded in high resolution from our website for non-commercial use (research/study, educational purposes, personal blogs and social media).

Would you like to use our images in a publication? Please mention our credit line: "Mauritshuis, The Hague."

Commercial use

Would you like to use our images for commercial purposes? We would be happy to discuss this with you. Please contact our marketing department at [email protected].

Download Image

Non-commercial use

All our images can be downloaded in high resolution from our website for non-commercial use (research/study, educational purposes, personal blogs and social media).

Would you like to use our images in a publication? Please mention our credit line: "Mauritshuis, The Hague."

Commercial use

Would you like to use our images for commercial purposes? We would be happy to discuss this with you. Please contact our marketing department at [email protected].

Two stages

The cannon’s original home was the royal palace of Kandy, where it was used for gun salutes to welcome guests. Two similar cannons from the same palace were discovered by the international research team at Windsor Castle, in the UK. Thanks to this discovery, it is now clear that the cannon’s decorations were added in two stages, as explained above. When the gun was cast, sometime between 1660 and 1680, the Netherlands wanted to strengthen its trading position in Sri Lanka. This meant that a good relationship with Kandy was important. It is possible that the cannon was gifted to the King of Kandy by the Dutch East India Company. The second decorative layer was commissioned by the Kandyan governor Lewke Disava in the 1740s, almost a century later. These decorations were applied as a tribute to the king, in hopes of gaining his favour.

Forgotten provenance

When the cannon arrived in the Netherlands, its backstory was changed. In Stadholder William V’s cabinet of curiosities, it was still described as a war trophy from Ceylon. Then, during the French rule of the Netherlands (1795-1815), it was suddenly labelled a Tunisian cultural artefact said to have been brought back by Admiral Michiel de Ruyter. When the cannon was exhibited at the Mauritshuis in the 19th century, it was displayed in a room dedicated to Dutch history (now Room 8). In 1880, it was discovered that the inscription on the cannon was in Sinhala, a Sri Lankan language. Only then did it become clear that the object was a piece of Sri Lankan heritage.