Paulus Potter & Jan Mijtens

In the 18th century, these two paintings were looted by the French from the collection now on show in the Mauritshuis in the 18th century.

Europe experienced unrest in the years prior to the French Revolution. Ordinary people were no longer willing to accept the privileges enjoyed by kings, aristocrats and the Church. The Netherlands was no exception: in 1787, patriots attempted to overthrow stadholder William V. This uprising was put down with military support from the king of Prussia, the stadholder’s brother-in-law.

When French revolutionary troops invaded the Netherlands in 1794, ‘to liberate the people’, William V fled to England, taking only his most prized possessions. The Netherlands was declared a sister republic of France, but in reality the country was occupied.

Much of the collection that William V left behind was seized and declared property of the French State in the Treaty of The Hague. Almost 200 paintings ended up in the Louvre in Paris. The many ‘artistic conquests’ brought Europe’s masterpieces together in that museum.

After Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815, the Netherlands retrieved as much looted art as possible. Many paintings were returned, including Cows Reflected in the Water by Paulus Potter. The Jan Mijtens’ painting remained in France, as did around 70 other works.

In 1818, the Netherlands ended efforts to bring home the remaining paintings. King William I designated the Mauritshuis as the destination for the art that did return from Paris. The empty spaces on this wall symbolise the pieces that never came back.

Stadholder Collection

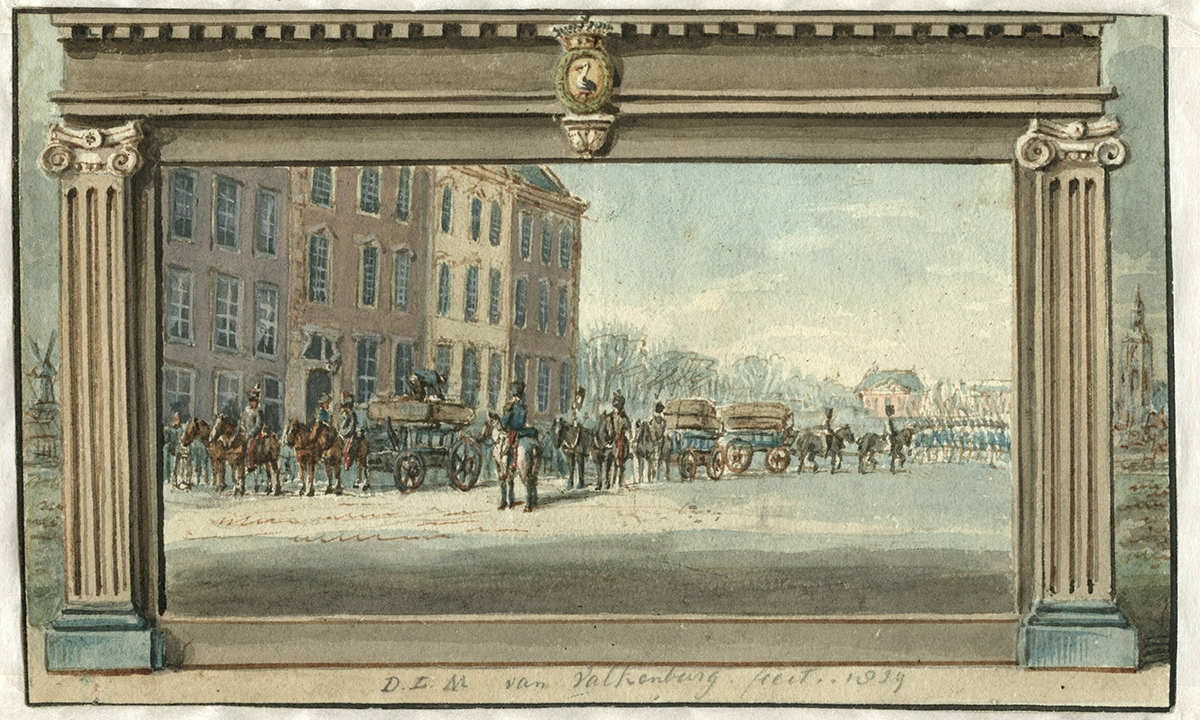

During the French invasion of 1795, Stadholder William V’s painting collection was exhibited in his gallery on Buitenhof in The Hague (now open to visitors as the Mauritshuis’s satellite location). The Netherlands’ first public museum had opened there in 1774, mainly featuring 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art. Most of the works on display came from William V; a small portion had been acquired by his father. The Oranges had been avid art collectors as early as the 17th century, but gradually their paintings had ended up abroad. Under the stewardship of William V, the Stadholder Collection was once again restored to its former princely splendour.

The Louvre

In 1793, the Louvre was transformed from a royal palace to a public museum, first known as the Muséum Central des Arts and later as the Musée Napoléon. According to the revolutionary ideal of equality, the confiscated art treasures that had formerly belonged to the king, the church and the nobility had to be made accessible to the public. In the following two decades, various ‘artistic conquests’ brought together the finest masterpieces from Europe and Egypt at the Louvre. The 194 paintings taken from William V’s gallery in The Hague were marked with the word “stat” (short for stadholder) after they arrived in France. Around 40 of the works were exhibited – the rest ended up in storage.

Appropriation through restoration

On their arrival in Paris, most of the stadholder’s paintings were in good condition. Only eight of the works underwent restorations in Paris, including Paulus Potter’s Cows Reflected in the Water, to prepare them for their new homes in various French museums. This can be seen as part of an “appropriation ritual”: by erasing any visible signs of use by previous owners, time was turned back, so to speak, to the moment the paintings left the easel. The French, convinced that they had become the rightful owners, were happy to invest in these restorations.

Return

After the French surrender of 1814, France’s stability became a priority in Europe. To avoid putting pressure on the newly crowned French king, Louis XVIII, no agreements on the restitution of stolen paintings were made at first. Only in November 1815 was it officially decided that all looted art still present in Paris had to be returned. In the meantime, however, many countries – including the Netherlands – had already taken matters into their own hands and retrieved works from the Louvre themselves. No agreements were ever made about the confiscated works of art that had been taken to other locations in France.

The French art grab prompted many European countries to reflect on their national heritage. How could priceless works of art best be protected from looting, decay and destruction? The painful fact that important Dutch paintings could only be seen in Paris during the French occupation had made it clear that the Netherlands’ national heritage was vulnerable, reinforcing patriotic sentiments. It is no surprise, then, that many national museums were founded during this period, both in the Netherlands and in other European countries, where repatriated works were displayed alongside other national art.