Rembrandt

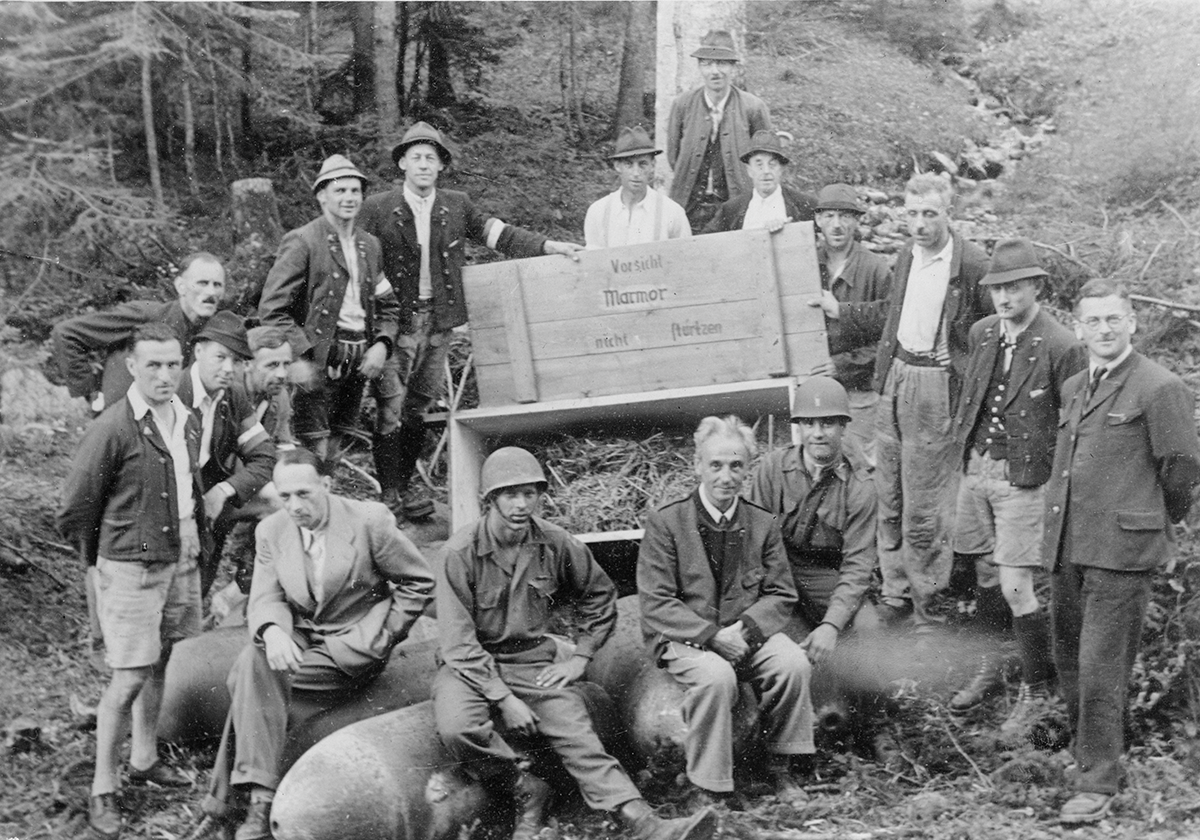

This self-portrait by Rembrandt was discovered in a salt mine in Austria in 1945. The VR experience allows you to see the mine with your own eyes.

Hitler’s staff had stored around 6,500 works of art in this salt mine, including masterpieces such as the Ghent Altarpiece by the Van Eyck brothers and Vermeer’s Astronomer. All works were meant for the Führer Museum that Hitler was planning to build in his birthplace Linz; the museum was never realised.

Before the war, this Rembrandt belonged to the Jewish Germans Ernest and Ellen Rathenau and was on permanent loan to the Rijksmuseum. The Rathenaus managed to flee from Germany to the Netherlands in the 1930s, and later to the UK and the USA. Unfortunately, their attempts to get the Rembrandt to safety were unsuccessful. The painting was looted by the Germans and stored in the mine.

In May 1940, the nazis began a methodical, large-scale operation to seize or force the sale of works of art, mostly from Jewish individuals. The Dutch national collections, on the other hand, were left untouched.

When Hitler was about to lose the war, the nazis came up with a plan to destroy the stolen treasures. The brave miners that you see in the VR experience managed to move the bombs just in time and save the art.

Eventually, many stolen works were recovered thanks to the ‘Monuments Men’, a group of the Allies with knowledge of art. After the war, Rembrandt’s self-portrait was part of the first official art transport to the Netherlands. The painting was returned to the Rathenau family, who sold it to the Mauritshuis in 1947.

‘German heritage’

Ernest and Ellen Rathenau had inherited this self-portrait from their grandfather, the well-known Berlin art collector Marcus Kappel. Kappel had previously pledged to donate the painting to the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in Berlin, but ended up reneging on this promise for financial reasons. In 1925, the Rathenaus gave their Rembrandt on loan to the Rijksmuseum. The Nazis saw this as a reason to confiscate the self-portrait in 1940: as part of the Kappel Collection, the painting was on a list of protected ‘German heritage’ that, according to the Nazis, should not have left the country – not even to be lent to the Rijksmuseum.

Anti-Jewish laws

Because the Nazis saw the Dutch as a Germanic ‘brother people’, they chose the strategy of ‘self-Nazification’. This meant that policies to persecute Jews in the Netherlands were implemented slowly, step by step, as it was believed that taking harsh anti-Jewish measures too quickly would create unnecessary unrest. From May 1942, Dutch Jews had to hand over their art and jewellery. That same year, the deportations to concentration camps began, and homes of deported Jews were emptied. Jewish owners also sold art to the Nazis, but in many cases they did so against their will. Artworks were traded for exit visas, for example, or they were used to buy people’s freedom.

The Monuments Men

In autumn 1943, several Allied art experts travelled to the front to protect Europe’s heritage and track down stolen art. The project was initiated by the US, but soon other Allies joined in. By the end of the war, hundreds of Nazi warehouses had been discovered. The artworks were inventoried and collected in depots, from where they could be returned to their countries of origin. From the Soviet-occupied zone and the later GDR, almost no private property was returned.

Return

On 8 October 1945, a special flight landed at Schiphol Airport. It was the first post-war art transport from Germany, and on board were 26 masterpieces, including Rembrandt’s self-portrait. As agreed by the Allies in 1943, the recovered treasures had to be sent back to their countries of origin first. After that, it was up to the respective countries to handle further returns to owners and heirs. In the Netherlands, the Rembrandt was returned to the Rathenaus shortly after the war. The siblings then sold the painting to the Mauritshuis in 1947.

Netherlands Art Property Foundation

After the war, art retrieved from Germany was managed by the Netherlands Art Property Foundation. From 1948, this foundation proactively tracked down owners and organised special exhibitions where people could look for their stolen property. Because of strict restitution requirements, however, many items were never returned – to claim an object, people had to provide proof of ownership and involuntary loss of possession, and pay 2.75% of the appraised value to cover expenses. In the early 1950s, the remaining artworks were deemed ‘ineligible for restitution’. They were auctioned off or included in the national NK Collection and then loaned to museums such as the Mauritshuis.