17. Out of the blue

Blue is my favourite colour, as you can see by my braided blue hair. The Girl also has something blue on her head. She wears an headscarf because Vermeer painted her as a tronie (a character head) wearing exotic clothing. Ultramarine, the brilliant blue pigment that he used to paint the headscarf, also has an exotic back story.

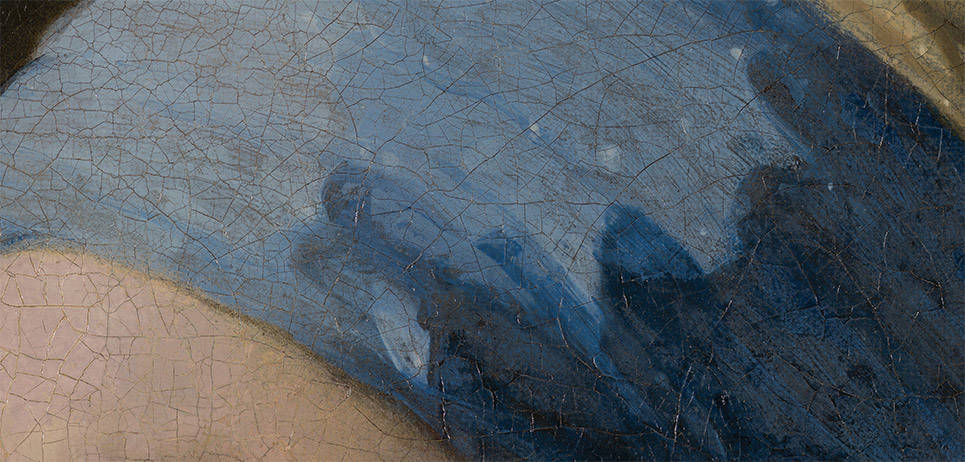

‘Beyond the sea’ with ultramarine

Ultramarine is made from the brilliant blue mineral, lazurite, found in the semiprecious stone lapis lazuli. It’s incredible that almost all of the ultramarine used in the history of art comes from one place on earth: a few mines high in the slopes of what is now north-east Afghanistan. The name ‘ultramarine’ literally means ‘beyond the sea’. Some of the lapis was shipped to Europe from Central Asia in boats, but most of it came by land along a very old trade route: the Silk Road.

Mining the lapis, carrying it down the mountain and transporting it to Europe was just the start of the extremely laborious process needed to make good ultramarine. The steps involved in extracting the pigment from the rock are reconstructed in this video. The rarity of the raw materials and this time-consuming extraction process meant that ultramarine was the most expensive pigment available: more valuable than gold.

How on earth did Vermeer afford it?

How on earth did Vermeer afford it? Apparently Vermeer only made a few paintings a year, and had many hungry kids to feed, so some scholars thought that Vermeer didn’t have a lot of money. Perhaps he had a patron or rich benefactor? Maybe he was better off than we assume.

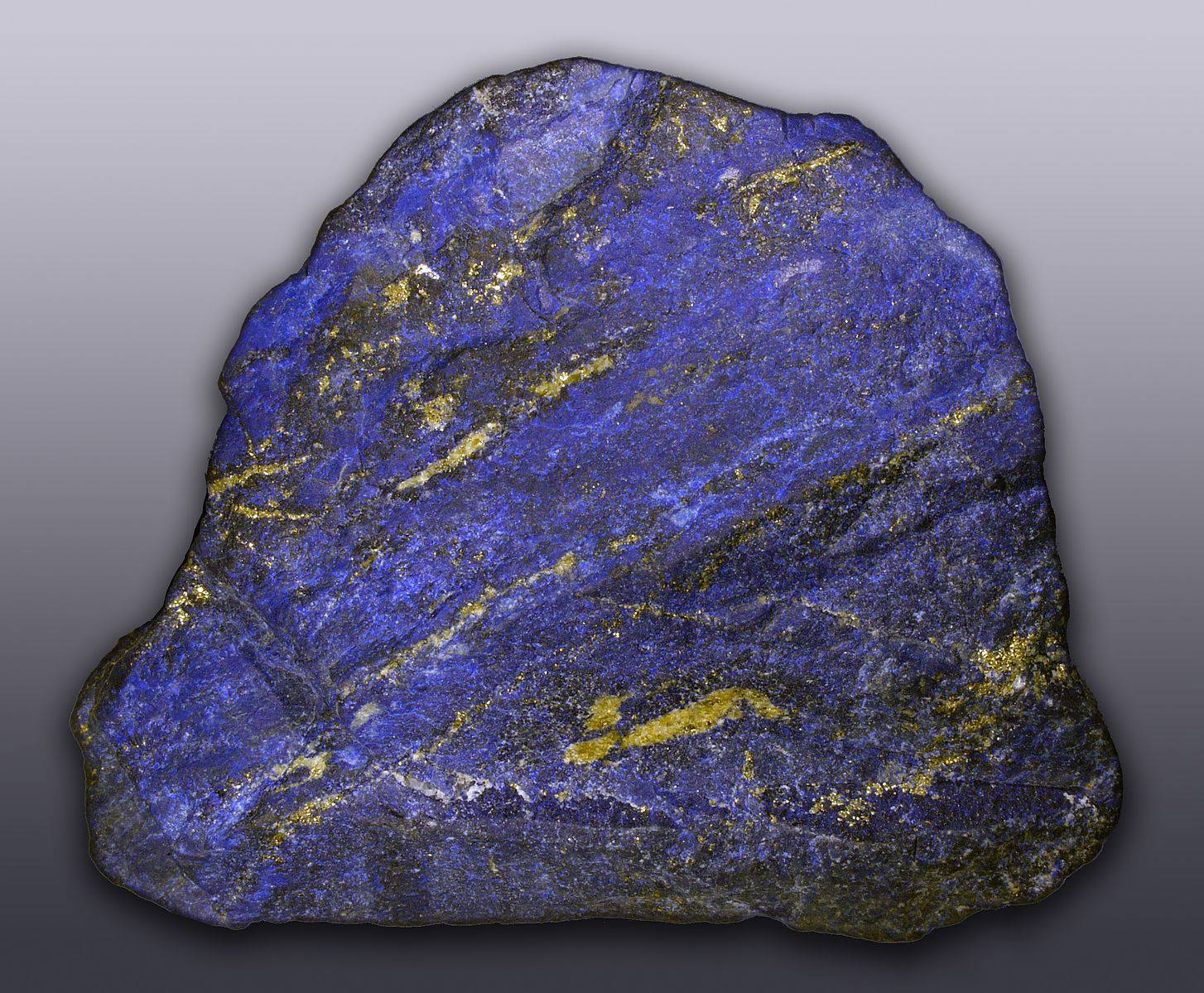

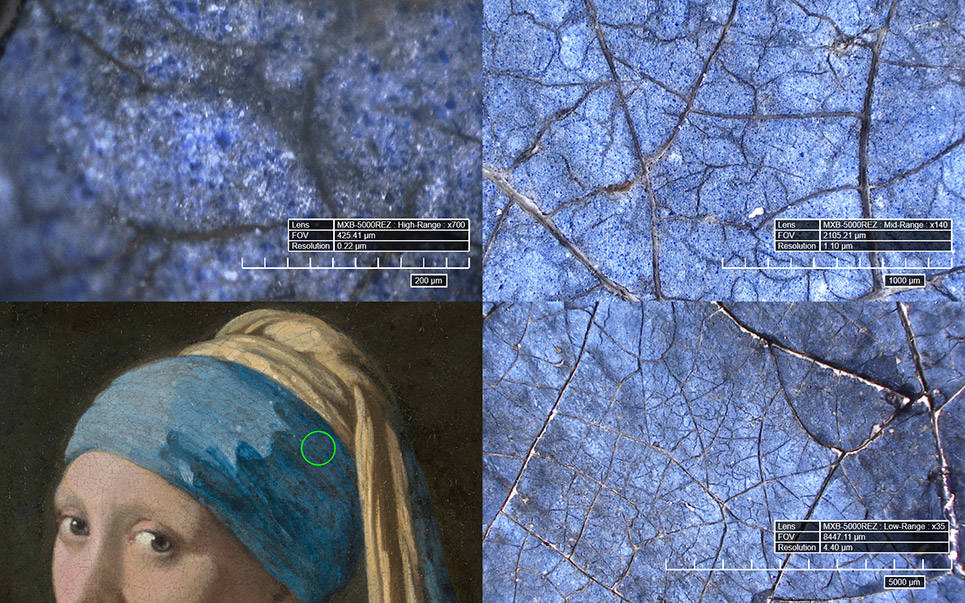

Wherever he got the ultramarine, we know that Vermeer used lots of it. Woman Reading a Letter (c. 1663) from the Rijksmuseum is full of ultramarine, from the woman’s dress to the shadows in the background. In the Girl with a Pearl Earring, he also mixed ultramarine into the shadows of her yellow jacket. You can see the bright blue particles in cross-sections from her clothing.

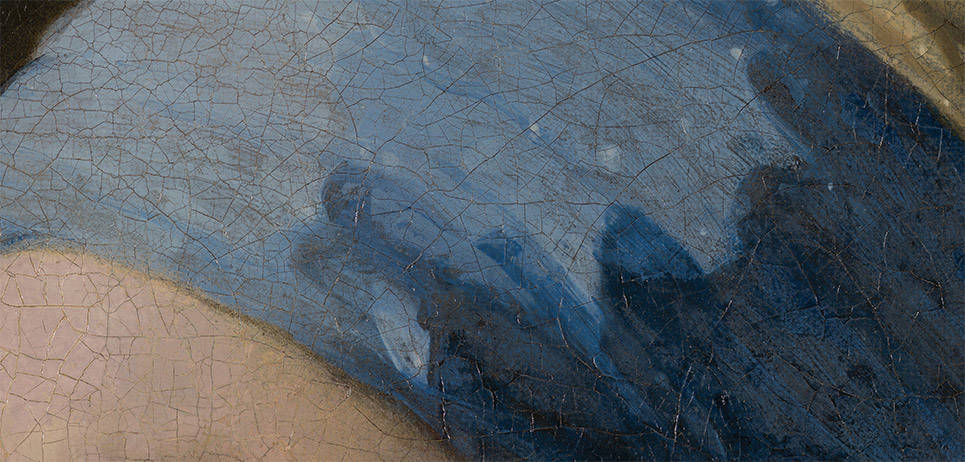

The Girl’s headscarf is a brilliant example of the different ways ultramarine can be used. The left side is an opaque light blue containing ultramarine and lead white. On the right side, there is a dark underlayer. To create a transition between the two halves, Vermeer applied a translucent glaze on top of both in a zigzag shape.

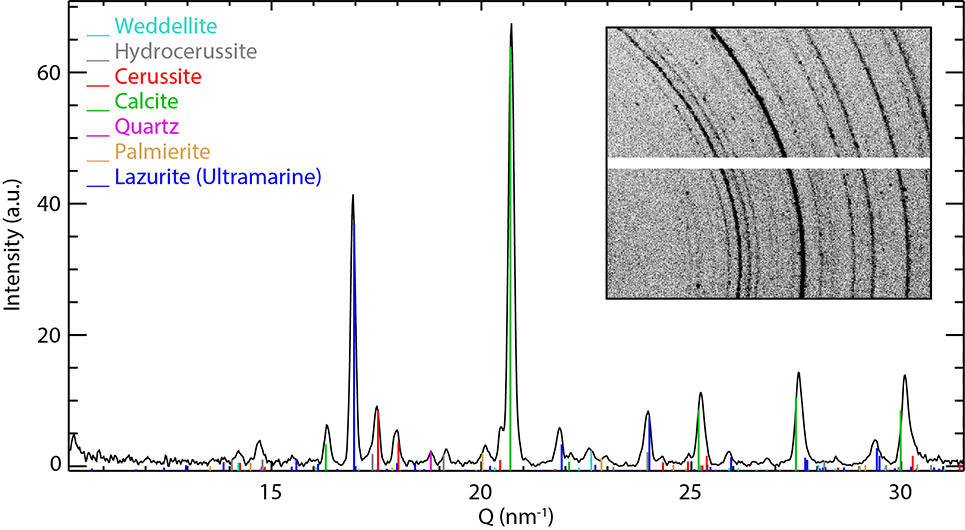

The shadow of the headscarf above her ear looks different now than it did when Vermeer painted it. The extent of possible degradation in the Girl’s headscarf is something we are researching as part of the Girl in the Spotlight project. Using the 3D digital microscope, we can inspect the surface in areas that seem to have degraded. With MA-XRPD we will learn more about the crystalline structure of the pigment, and how it has changed over time. Degradation of paint layers leads to new chemical compounds being formed on or close to the paint surface, altering its appearance. In the dark blue, MA-XRPD detected small amounts of two of these compounds: palmierite and weddellite.

Indigo: it’s in your jeans

In an earlier blog entry, I explained that the dark background around the Girl was originally a very dark green colour. On top of a black underlayer, Vermeer applied a green glaze containing weld (yellow) and indigo (dark blue).

Indigo is a dye made from the leaves of fermented indigo plants. The word ‘indigo’ means from ‘coming from India,’ although India was only one of the places where the plants grew. In the early 17th century, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was formed. This caused a huge increase in the amount of indigo imported from India. But also, as part of the Atlantic trade, the Dutch also established indigo plantations in the tropics. A Dutch newspaper from the decades around when the Girl with a Pearl Earring was painted lists indigo among the cargo of Dutch boats coming from the West Indies. It was shipped along with tobacco, pepper, tea, nutmeg, sugar and ginger. Like these ‘spices’, indigo was usually sold in bulk as ‘cakes’, but could also be sold as smaller ‘lumps’.

Unfortunately, we can’t (yet) scientifically prove whether the indigo in the Girl comes from a source in the India, the New World, or other parts of the globe. Indigo belongs to a huge number of different plant families (with almost 800 different species). It’s difficult to chemically distinguish between them, so we can’t be sure where Vermeer’s indigo came from.

Indigo was mostly used to dye clothing. (Today, a synthetic indigo is used to dye blue jeans). In the 17th-century Netherlands, several qualities of indigo were available at retailers who specialised in painting materials. Even though it was a mid-priced pigment – a lot cheaper than ultramarine – the highest qualities could be pricey, and its price fluctuated a lot due to irregular supply by sea.

When used as a pigment in oil paintings, indigo can lose its colour. Margriet van Eikema Hommes, a researcher from the RCE who studies colour change in paintings, mentions that historical texts warned against using indigo in oil because it fades when exposed to sunlight. In his ‘painter’s manual’, T.T. De Mayerne wrote: ‘Indigo is of no use in oil and fades immediately,’ but he also gives some instructions on how to purify indigo, and how to improve its lightfastness by mixing it with calcified rock alum. The chemical element aluminium (Al) – a component of alum – was detected in samples from the background of the Girl using SEM-EDX. Perhaps Vermeer was optimistic that his indigo would last the test of time. Unfortunately, fading of indigo is likely one of the factors that has caused the background of the Girl to change since he painted it.

References

- Kirby, Jo, Susie Nash, Joanna Cannon (eds.) (2010) Trade in Artists’ Materials: Markets and commerce in Europe to 1700, Archetype, London.

- Van Eikema Hommes, Margriet (2004) ‘Indigo as a pigment in oil painting and its fading problems,’ Changing Pictures: Discoloration in 15th-17th-century oil paintings, Archetype, London, pp. 91-170.

- De Mayerne, Theodore Turquet (1620-1646) ‘De Mayerne Manuscript’: Pictoria, sculptoria et quae subalternarum atrium, Sloane MS 2052, British Library. Fol. 4v mentions the fading of indigo when exposed to sunlight. Mixing indigo with calcified rock alum and nut oil is on fol. 144v.

Acknowledgements

- MA-XRPD: AXES team (University of Antwerp)

- Research into ultramarine disease: Alessa Gambardella (Rijksmuseum, with funding from AkzoNobel) and Katrien Keune (Rijksmuseum)

- Digital microscopy: Emilien Leonhardt and Vincent Sabatier (Hirox Europe)

- UHPLC analysis and archival research about indigo: Art Ness Proaño Gaibor (Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands (RCE)), with additional information from Maarten van Bommel (University of Amsterdam)