13. Background check

When you stand in front of the Girl with a Pearl Earring, the dark background appears to recede, and the Girl herself is – visually and emotionally – closer to you. The contrast between the figure and the background also makes her look more 3-dimensional, and focuses your attention on the brightest areas of her face and earring. Apparently the trend for using dark backgrounds for portraits started with Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), then the convention was adopted by Dutch artists.

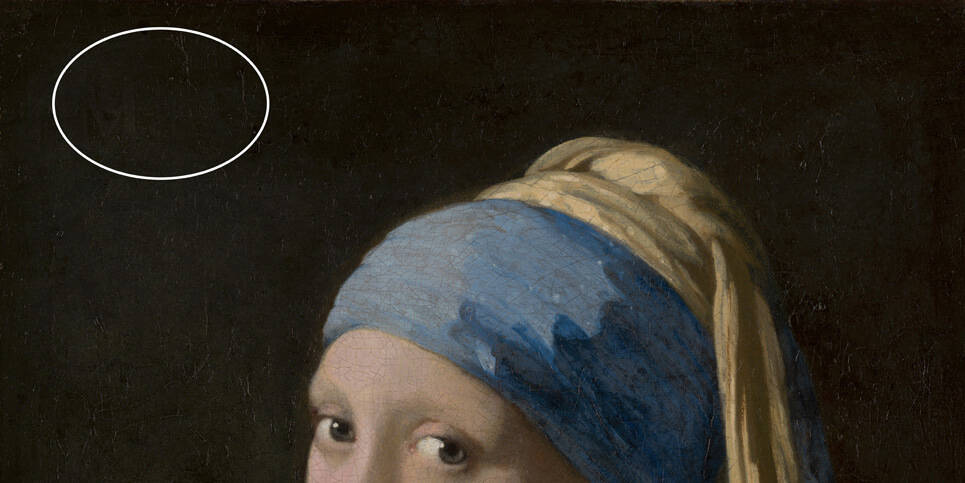

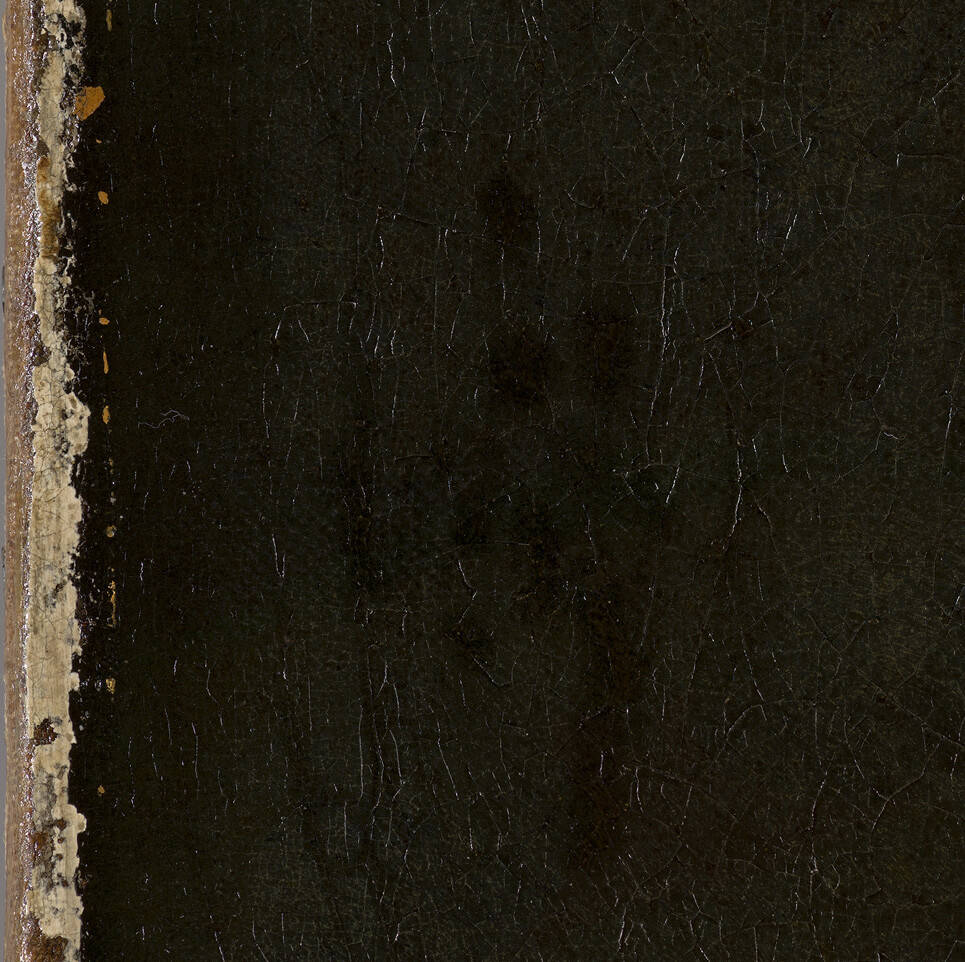

The background is usually described as ‘black’ or ‘dark’, but did you know it was originally a very dark green colour? Did you notice Vermeer’s signature in the top left corner?

‘Wel geblaut, wel gewaut’

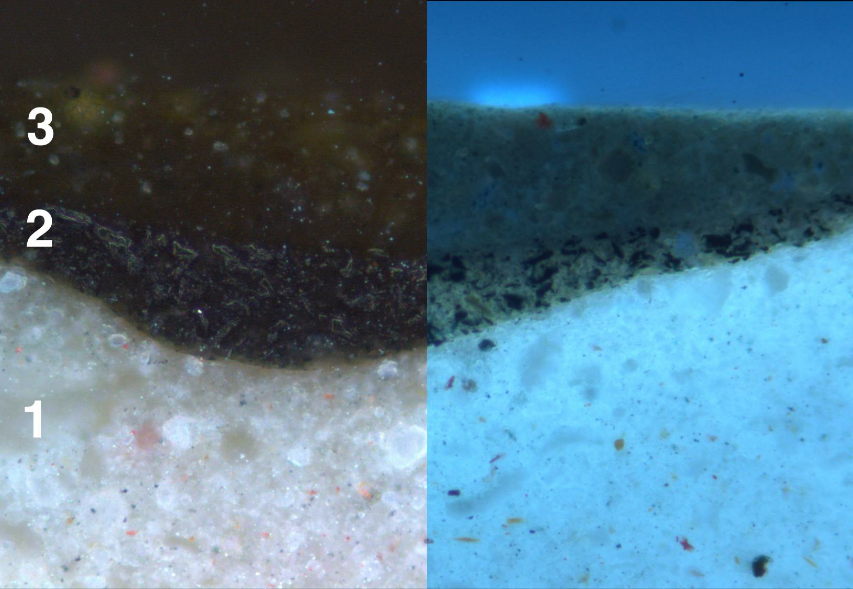

Cross-sections and examination under the microscope showed that Vermeer built up the background in several layers. On top of the ground (1), he applied a layer of black (2). They described it as ‘bone black’, but recent analysis at very high magnification using SEM/EDX and FIB-TEM has shown that it contains charcoal black. On top of this, Vermeer painted a green glaze (3): a translucent layer of paint containing indigo (blue) and weld (yellow).

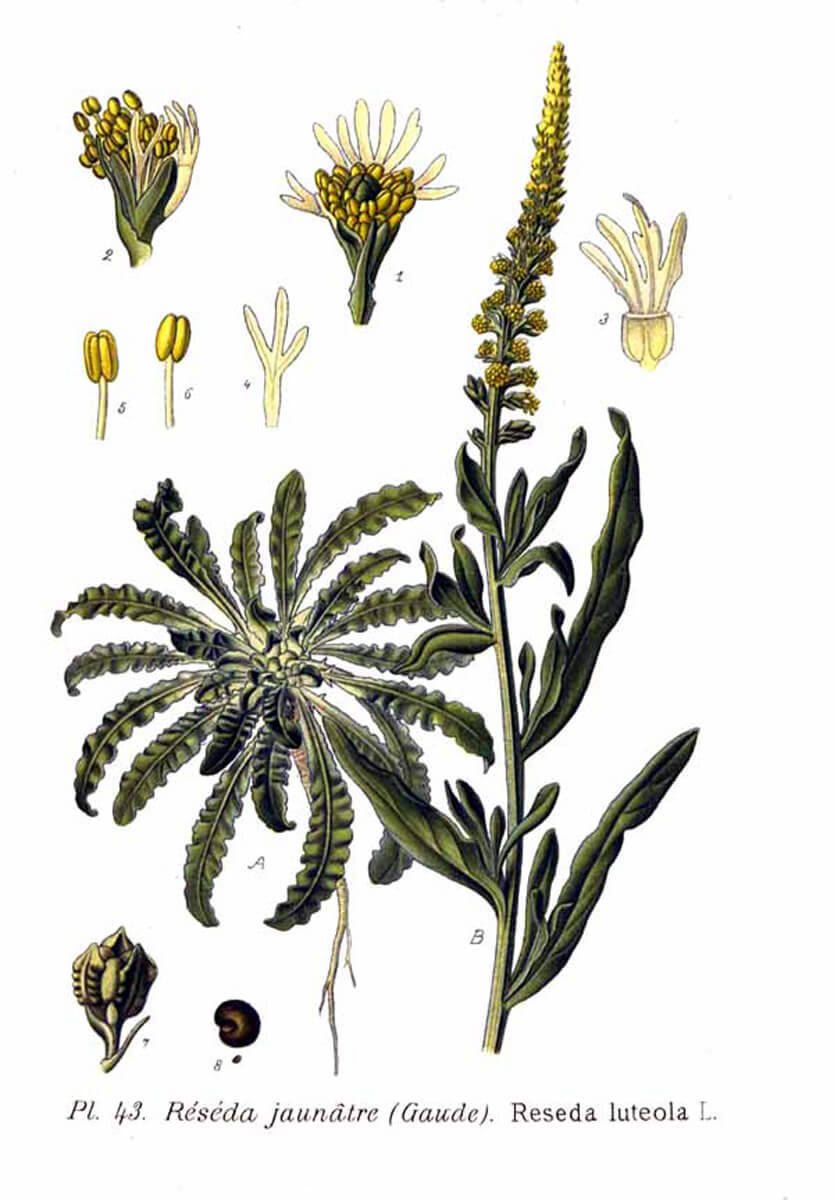

In 17th-century Holland, people used the expression ‘wel geblaut, wel gewaut’ to mean: well-dyed with blue (indigo) and well-dyed with yellow (weld). The combination of blue and yellow to make green was used to dye clothes and fabrics. I’ll discuss indigo along with the other blue pigments in a later blog, so here I’ll concentrate on the yellow colourant: weld.

Weld is a natural yellow dye made from the plant known as ‘Dyer’s rocket’: Reseda luteola L.. The flowers, stem and leaves can all be used, but apparently the best quality weld comes from the flowers. This plant grew all over Europe, and is both one of the oldest and most widely-used dyes. To turn the weld into a yellow pigment, the dye had to be precipitated onto a white powder, in this case, chalk.

Organic yellow lakes are hard to identify and to analyse because they fade when exposed to light. This might be why there are blue trees in Vermeer’s Little Street (ca. 1658) at the Rijksmuseum. Sometimes it’s possible to confirm the presence of a ‘vanished’ lake pigment if the substrate (chalk) still remains and can be detected using scientific analysis. Weld in the Girl with a Pearl Earring was first identified in the 1994 using a chromatographic technique called HPLC (high-performance liquid chromatography). As part of the recent re-examination of the samples, an enhanced version of this technique detected the luteolin and apigenin components from the weld.

For the TV show Het Geheim van de Meester (Secret of the Master), Charlotte Caspers reconstructed the Girl with a Pearl Earring. She made some tests layering a weld and indigo glaze on top of a black underlayer to show what the background might have originally looked like.

One reason that the background looks patchy and mottled today is because both of the organic colourants - indigo and weld - have faded due to light exposure. The paint in the background could have deteriorated for other reasons too: environmental conditions where it was hanging in the past, previous restorations, and/or darkening of the oil medium.

One area of the background that might jump out at you is a shiny patch near the left edge in the middle of the painting. This is actually the best-preserved part of the background, because old restoration materials shielded it from moisture and light for decades. During the 1994 restoration, the conservators decided to leave this area as-is, as it is closer to how Vermeer would originally have intended the background to look.

Signed, sealed, delivered

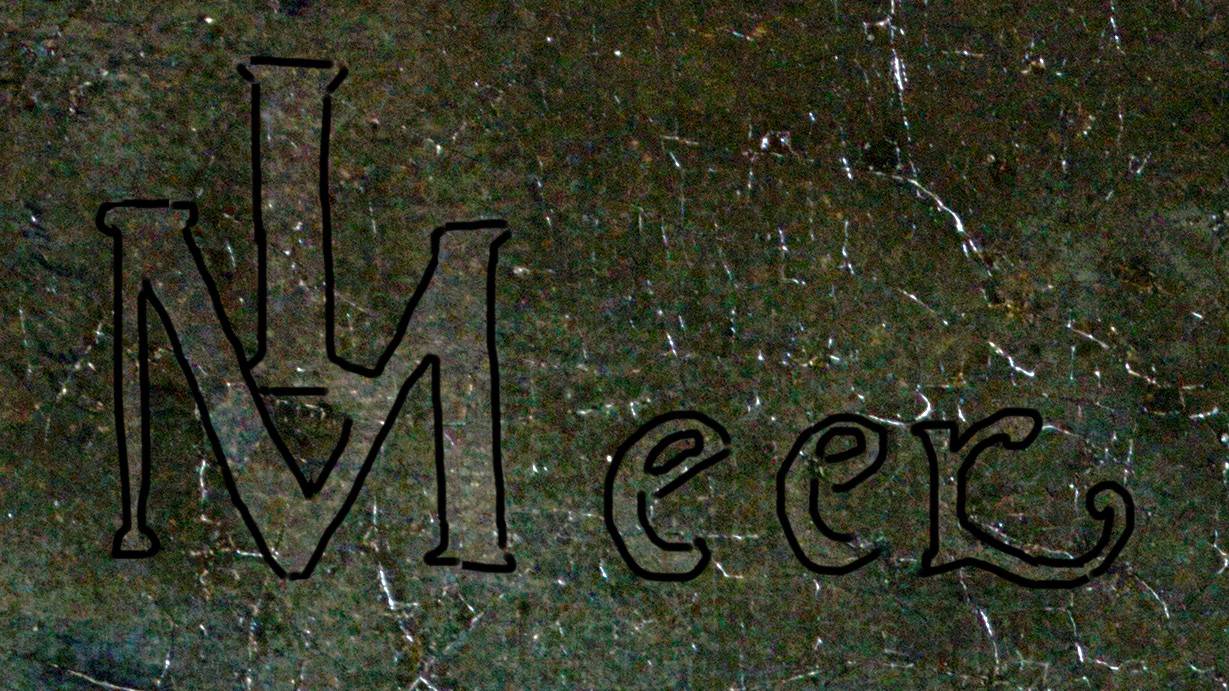

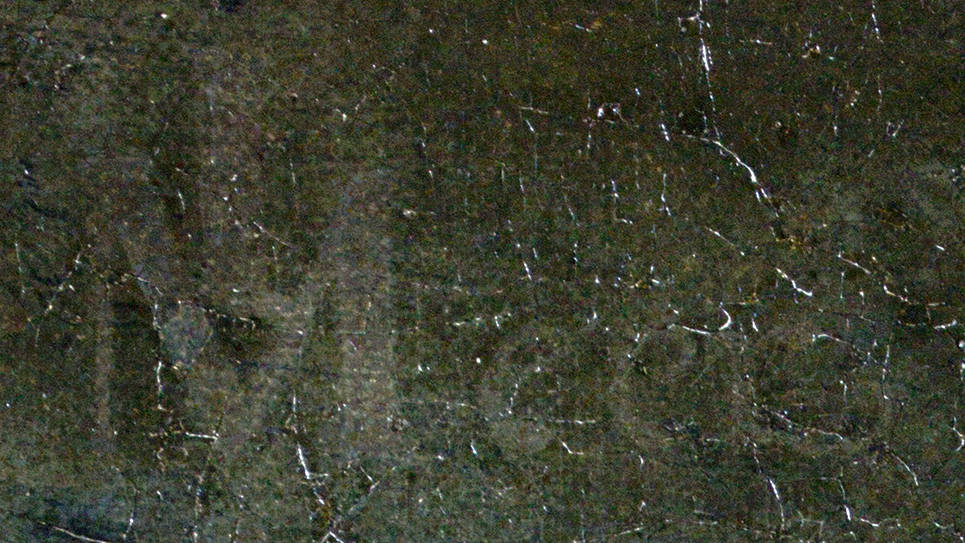

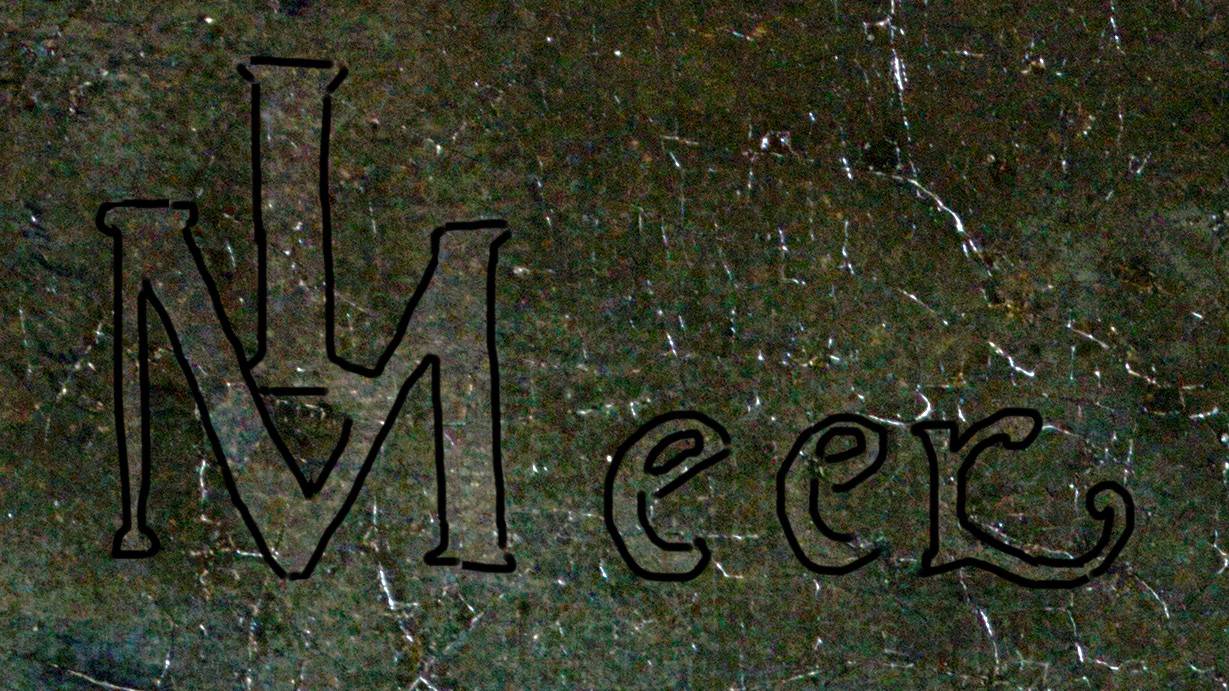

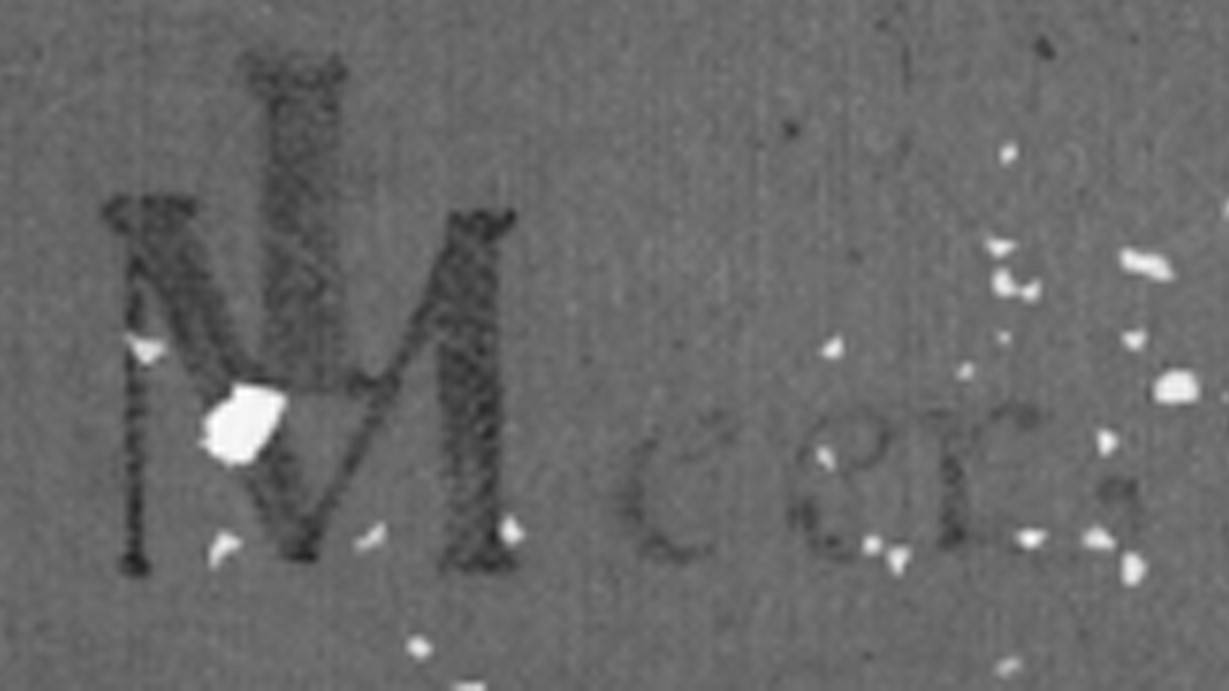

Vermeer signed the Girl with a Pearl Earring with his monogram ‘IVMeer’ in the top left corner (circled on fig. 13a). The letters ‘IVM’ are in ligature, i.e. they are connected together. Vermeer used several signatures throughout his career, but the placement and style of this one is most similar to the Study of a Young Woman from the Metropolitan Museum.

The signature is almost invisible with the naked eye, but you can see it in the calcium (Ca) map made by MA-XRF.

References

- Groen, Karin M., Van der Werf, Inez D., Van den Berg, Klaas Jan, Boon, Jaap ‘Scientific examination of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring,’ In: Vermeer Studies: Studies in the History of Art, edited by Ivan Gaskell and Michiel Jonker, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., Yale University Press, New Haven/London, 1998. [online version]

- Reseda luteola (Wikipedia)

- Zegeling, Mark and Marc Pos (2017) Het Geheim van de Meester, Markmedia & Art.

- Van Eikema Hommes, Margriet (2004) ‘Indigo as a pigment in oil painting and its fading problems, Changing Pictures: Discoloration in 15th-17th-century oil paintings, Archetype, London, pp. 91-170.

- Johannes Vermeer: Signatures,’ Essential Vermeer website

Acknowledgements

- Reconstructions: Charlotte Caspers

- UHPLC analysis of weld: Art Ness Proaño Gaibor (Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands (RCE))

-

MA-XRF: Annelies van Loon (Mauritshuis/Rijksmuseum)